Please stop by and enjoy the December edition of the Catholic Homeschool Carnival at O Night Divine, and be sure to thank Mary Ellen for her great work!

Relatively speaking, it is the Gospel that has the mysticism and the Church that has the rationalism. As I should put it, of course, it is the Gospel that is the riddle and the Church that is the answer. But whatever be the answer, the Gospel as it stands is almost a book of riddles.On the whole, he tries to show us the story of the Gospel from the outside - as if someone had never read it before. He looks at all kinds of assumptions and accusations people make regarding the Gospels and shows quite convincingly that the Gospels can't be pinned down to such narrow views. This is not the stuff of platitudes, or madness or writings that are only relevant to people of that time.

Whatever else is true, it is emphatically not true that the ideas of Jesus of Nazareth were suitable to his time, but are no longer suitable to our time. Exactly how suitable they were to his time is perhaps suggested in the end of the story.(I love his understated style here.)

He never used a phrase that made his philosophy depend even upon the very existence of the social order in which he lived. He spoke as one conscious that everything was ephemeral, including the things that Aristotle thought eternal. By that time the Roman Empire had come to be merely the orbis terrarum, another name for the world. But he never made his morality dependent on the existence of the Roman Empire or even on the existence of the world. 'Heaven and earth shall pass away; but my words shall not pass away.'One last zinger from this chapter...

The truth is that when critics have spoken of the local limitations of the Galilean, it has always been a case of the local limitations of the critics. He did undoubtedly believe in certain things that one particular modern sect of materialists do not believe. But they were not things particularly peculiar to his time. It would be nearer the truth to say that the denial of them is quite particular to our time.

Now each of these explanations in itself seems to me singularly inadequate; but taken together they do suggest something of the very mystery which they miss. There must surely have been something not only mysterious but many-sided about Christ if so many smaller Christs can be carved out of him. If the Christian Scientist is satisfied with him as a spiritual healer and the Christian Socialist is satisfied with him as a social reformer, so satisfied that they do not even expect him to be anything else, it looks as if he really covered rather more ground than they could be expected to expect.

Revised and updated in November 2009 (particularly with YouTube videos) from my original post in 2006.

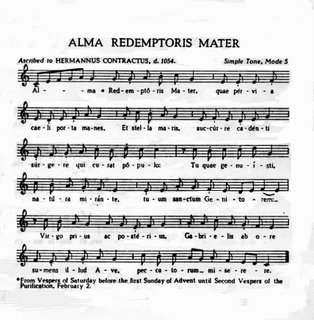

Revised and updated in November 2009 (particularly with YouTube videos) from my original post in 2006. Here's a decent way to learn the traditional chant:

Here's a decent way to learn the traditional chant:85-100% You must be an autodidact, because American high schools don't get scores that high! Good show, old chap!

Do you deserve your high school diploma?

Create a Quiz

Wow! I just finished this new release by Dawn Eden and it's quite powerful.

Wow! I just finished this new release by Dawn Eden and it's quite powerful.If you want to receive the love for which you hunger, the first step is to admit to yourself that you have that hunger, with everything it entails - weakness, vulnerability, the feeling of an empty space inside. To tell yourself simply, "I'll be happy once I have a boyfriend," is to deny the depth and seriousness of your longing. It turns the hunger into a superficial desire for flesh and blood when what we really want is someone to share divine love with us - to be for us God with skin on. (pg. 28)

I spent many years of my life being single. I have nothing to show for it except the ability to toss my hair fetchingly and a mental catalog of a thousand banal things to say to fill the awkward, unbearably lonely moments between having sex and putting my clothes back on. You never see those moments in TV or movies, because they strike to the heart of the black hole that casual sex can never fill. (pg. 25)

The idea of love as a presence and not a passion is tantalizingly similar to the definition of faith given to us in Hebrews: "the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen". It gives love a tangibility and a certainty that we normally do not feel in everyday life, save for the moments when we contemplate those dearest to us. More than that, love as a presence suggests something that's inescapable, without form - something that could conceivably fill everything. (pg. 90)

Taking my complaint very seriously, Mom advised me to read up on what Christians call spiritual warfare - especially Paul's words in 2 Corinthians, where he distinguishes between physical enemies and spiritual enemies: "For though we walk in the flesh, we do not war according to the flesh. For the weapons of our warfare are not carnal but mighty in God for pulling down strongholds, casting down arguments and every high thing exalts itself against the knowledge of God, bringing every thought into captivity to the obedience of Christ."

Bringing every thought into captivity means being the master of one's thoughts and passions instead of being mastered by them. It made sense to me; that was what I needed to do. If Paul knew what he was talking about, then I needed help - because I was locked, however unwillingly, in a spiritual battle. (pgs. 171-172)

Instead of passive resignation, one must commit to active resolution: the determination to never miss an opportunity to share His grace with others.

This is something that can be done every minute of every day. God's grace may be found in every experience, whether it's a happy or painful one. We discover His grace by stepping out in faith - realizing our dependence on the Lord, and allowing ourselves to risk disappointment, so that we might be open to every blessing He has in store for us. (pg. 195)

If your light shines through everything you do, from the greatest thing to the smallest, then it will be impossible for anyone to miss it. This is why the self-advertisement encouraged by the singles industry is counterproductive. When you focus the spotlight on yourself, no one can see how beautifully your light illuminates those around you.

It took me years to learn that lesson. (pg. 108)

So writes John Wild, the American scholar and expert on Plato: "The Sophist appears as a true philosopher, more so than the philosopher himself." (pg. 29)

"Is it not obvious", he wonders in his dialogue Phaedrus, "that even those who have a genuine message of truth and reality must first court the favor of the people so they will listen at all? Is there not such a thing as seduction to the truth?"

Be this as it may - this much remains true: wherever the main purpose of speech is flattery, there the word becomes corrupted and necessarily so. And instead of genuine communication, there will exist something for which domination is too benign a term; more appropriately we should speak of tyranny, of despotism.

Public discourse, the moment it becomes basically neutralized with regard to a strict standard of truth, stands by its nature ready to serve as an instrument in the hands of any ruler to pursue all kinds of power schemes. Public discourse itself, separated from the standard of truth, creates on its part, the more it prevails, an atmosphere of epidemic proneness and vulnerability to the reign of the tyrant.

The abuse of political power is fundamentally connected with the sophistic abuse of the word.

Consequently, one may be entirely knowledgeable about a thousand details and nevertheless, because of ignorance regarding the core of the matter, remain without basic insight. This is a phenomenon in itself already quite astonishing and disturbing. Arnold Gehlen labeled it "a fundamental ignorance, created by technology and nourished by information."

Heavenly Father, from whom every family in heaven and earth takes its name, we humbly ask that you sustain, inspire and protect your servant, Pope Benedict XVI as he goes on pilgrimage to Turkey - a land to which St. Paul brought the Gospel of your Son; a land where once the Mother of your Son, the seat of Wisdom, dwelt; a land where faith in your Son's true divinity was definitively professed. Bless our Holy Father, who comes as a messenger of truth and love to all people of faith and good will dwelling in this land so rich with history. In the power of the Holy Spirit, may this visit of the Holy Father bring about deeper ties of understanding, cooperation and peace among Roman Catholics, the Orthodox, and those who profess Islam. May the prayers and the events of these historic days greatly contribute both to greater accord among those who worship you, the living and true God, and also to peace in our world so often torn apart by war and sectarian violence.

We also ask, O Heavenly Father, that you watch over and protect Pope Benedict and entrust him to the loving care of Mary, under the title of Our Lady of Fatima, a title cherished both by Catholics and Muslims. Through her prayers and maternal love, may Pope Benedict be kept safe from all harm as he prays, bears witness to the Gospel, and invites all peoples to a dialogue of faith, reason and love. We make our prayer through Christ Our Lord. Amen.

| What American accent do you have? Your Result: The West Your accent is the lowest common denominator of American speech. Unless you're a SoCal surfer, no one thinks you have an accent. And really, you may not even be from the West at all, you could easily be from Florida or one of those big Southern cities like Dallas or Atlanta. | |

| The Midland | |

| Boston | |

| North Central | |

| The Inland North | |

| Philadelphia | |

| The South | |

| The Northeast | |

| What American accent do you have? Take More Quizzes | |

The deadline for submissions to our December carnival, is fast-approaching. Please send in those Advent and Christmas ideas, stories, reviews etc. (prayer requests are also welcome) by November 26th. This carnival will be hosted by O Night Divine: A Blog Devoted to the Celebration of Christmas on December 1st!

The deadline for submissions to our December carnival, is fast-approaching. Please send in those Advent and Christmas ideas, stories, reviews etc. (prayer requests are also welcome) by November 26th. This carnival will be hosted by O Night Divine: A Blog Devoted to the Celebration of Christmas on December 1st!

"He good guy. He get bad guys. He not have sword. He have pockets!"

America may be a caricture of England. But in the gravest college, in the quietest country house of England, there is the seed of the same essential madness that fills Dickens's book, like an asylum, with brawling Chollops and raving Jefferson Bricks. That essential madness is the idea that the good patriot is the man who feels at ease about his country. This notion of patriotism was unknown in the little pagan republics where our European patriotism began. It was unknown in the Middle Ages. In the eighteenth century, in the making of modern politics, a "patriot" meant a discontented man. It was opposed to the word "courtier," which meant an upholder of the status quo. In all other modern countries, especially in countries like France and Ireland, where real difficulties have been faced, the word "patriot" means something like a political pessimist. This view and these countries have exaggerations and dangers of their own...

The thing which is rather foolishly called the Anglo-Saxon civilization is at present soaked through with a weak pride. It uses great masses of men not to procure discussion but to procure the pleasure of unanimity; it uses masses like bolsters. It uses its organs of public opinion not to warn the public, but to soothe it. It really succeeds not only in ignoring the rest of the world, but actually in forgetting it...

Martin Chuzzlewit's America is a mad-house: but it is a mad-house we are all on the road to. For completeness and even comfort are almost definitions of insanity. The lunatic is the man who lives in a small world but thinks it is a large one: he is the man who lives in a tenth of the truth, and thinks it is the whole. The madman cannot conceive any cosmos outside a ceratin tale or conspiracy or vision. Hence the more clearly we see the world divided into Saxons and non-Saxons, into our splendid selves and the rest, the more certain we may be that we are slowly and quietly going mad. The more plain and satisfying our state appears, the more we may know that we are living in an unreal world. For the real world is not satisfying. The more clear become the colours and facts of Anglo-Saxon superiority, the more surely we may know we are in a dream. For the real world is not clear or plain. The real world is full of bracing bewilderments and brutal surprises. Comfort is the blessing and the curse of the English, and of Americans of the Pogram type also. With them it is a loud comfort, a wild comfort, a screaming and capering comfort; but comfort at bottom still. For there is but an inch of diference between the cushioned chamber and the padded cell.

...the purpose in this place is merely to sum up the combination of ideas that make up the Christian and Catholic idea, and to note that all of them are already crystallised in the first Christmas story. They are three distinct and commonly contrasted things which are nevertheless one thing; but this is the only thing which can make them one.1. "the human instinct for a heaven that shall be as literal and almost as local as a home"

It gets every kind of man to fight for it, it gets every kind of weapon to fight with, it widens its knowledge of the things that are fought for and against with every art of curiosity or sympathy; but it never forgets that it is fighting. It proclaims peace on earth and neer forgets why there was war in heaven.

This is the trinity of truth symbolised here by the three types in the old Christmas story; the shepherds and the kings and that other king who warred upon the children. It is simply not true to say that other religions and philosophies are in this respect its rivals. It is not true to say that any one of them combines these characters; it is not true to say that any one of them pretends to combine them.

No other birth of a god or childhood of a sage seems to us to be Christmas or anything like Christmas. It is either too cold or too frivolous, or too formal and classical, or too simple and savage, or too occult and complicated. Not one of us, whatever his opinions, would ever go to such a scene with the sense that he was home. He might admire it because it was poetical, or because it was philosophical, or any number of other things in separation; but not because it was itself. The truth is that there is a quite peculiar and individual character about the hold of this story on human nature; it is not in its psychological substance at all like a mere legend or the life of a great man.

It does not exactly in the ordinary sense turn our minds to greatness; to those extensions and exaggerations of humanity which are turned into gods and heroes, even by the healthiest sort of hero-worship. It does not exactly work outwards, adventurously, to the wonders to be found at the ends of the earth. It is rather something that surprises us from behind, from the hidden and personal part of our being; like that which can sometimes take us off our guard int he pathos of small objects or the blind pieties of the poor. It is rather as if a man had found an inner room in the very heart of his own house, which he had never suspected; and seen a light from within. It is as if he found something at the back of his own heart that betrayed him into good.

It is not made of what the world would call strong materials; or rather it is made of materials whose strength is in that winged levity with which they brush us and pass. It is all that is in us but a brief tenderness that is there made eternal; all that means no more than a momentary softening that is in some strange fashion become a strengthening and a repose; it is the broken speech and the lost word that are made positive and suspended unbroken; as the strange kings fade into a far country and the mountains resound no more with the feet of the shepherds; and only the night and the cavern lie in fold upon fold over something more human than humanity.

This makes SO much sense to me! Hilda Van Stockum was a major lifeline that helped me get through the tougher earlier years of raising a large family, homeschooling, dealing with massive home projects, the frustrations and challenges of working with some children with "special needs", a husband with a large commute, years with only one car, long winters in a teeny house, financial stress, the pressures of others who thought we were crazy and didn't understand and all the rest. There was a LOT of joy too, of course, but we had our share of tough days. Her book Friendly Gables, especially, was one that I ended up pulling out to read to the kids when we were having a bad day. It worked such wonders for me and for the kids! This experience firmly convinced me of the value of good children's books for parents to read!

This makes SO much sense to me! Hilda Van Stockum was a major lifeline that helped me get through the tougher earlier years of raising a large family, homeschooling, dealing with massive home projects, the frustrations and challenges of working with some children with "special needs", a husband with a large commute, years with only one car, long winters in a teeny house, financial stress, the pressures of others who thought we were crazy and didn't understand and all the rest. There was a LOT of joy too, of course, but we had our share of tough days. Her book Friendly Gables, especially, was one that I ended up pulling out to read to the kids when we were having a bad day. It worked such wonders for me and for the kids! This experience firmly convinced me of the value of good children's books for parents to read!  Now the big questions for me (and I do worry myself over these) run more along the lines of how to try and help beginning homeschoolers who are overwhelmed with all the choices and possibilities and decisions to get a good start through my work on the web and homeschool workshops; to make sure I don't over-universalize my own personal experience; and things like that. Last summer when I was trying to finish up two talks on homeschooling and kept running into mental blocks or self-doubts it was Chesterton that I turned to. I finished both Heretics and Orthodoxy in the two or three weeks before the Minnesota Conference and they were *just* what I needed.

Now the big questions for me (and I do worry myself over these) run more along the lines of how to try and help beginning homeschoolers who are overwhelmed with all the choices and possibilities and decisions to get a good start through my work on the web and homeschool workshops; to make sure I don't over-universalize my own personal experience; and things like that. Last summer when I was trying to finish up two talks on homeschooling and kept running into mental blocks or self-doubts it was Chesterton that I turned to. I finished both Heretics and Orthodoxy in the two or three weeks before the Minnesota Conference and they were *just* what I needed.This sense that the world had been conquered by the great usurper, and was in his possession, has been much deplored or derided by those optimists who identify enlightenment with ease. But it was responsible for all that thrill of defiance and a beautiful danger that made the good news seem to be really both good and new. It was in truth against a huge unconscious usurpation that it raised a revolt, and originally so obscure a revolt. Olympus still occupied the sky like a motionless cloud moulded into many mighty forms; philosophy still sat in the high places and even on the thrones of the kings, when Christ was born in the cave and Christianity in the catacombs.

In both cases we may remark the same paradox of revolution; the sense of something despised and of something feared. The cave in one aspect is only a hole or corner into which the outcasts are swept like rubbish; yet in the other aspect it is a hiding-place of something valuable which the tyrants are seeking like treasure. In one sense they are there because the innkeeper would not even remeber them, and in another because the king can never forget them.

We have already noted that this paradox appeared also in the treatment of the early Church. It was important while it was still insignificant, and certainly while it was still impotent. It was important solely because it was intolerable; and in that sense it is true to say that it was intolerable because it was intolerant. It was resented, because, in its own still and almost secret way, it had declared war. It had risen out of the gorund to wreck the heaven and earth of heathenism. It did not try to destroy all that creation of gold and marble; but it contemplated a world without it. It dared to look right through it as though the gold and marble had been glass.

Those who charged the Christians with burning down Rome with firebrands were slanderers; but they were at least far nearer to the nature of Christianity than those among the moderns who tell us that the Christians were a sort of ethical society, being martyred in a languid fashion for telling men they had a duty to their neighbors, and only mildly disliked because they were meek and mild.

Now we come to the blunt accusation that Catholics are sinners and idolaters because of our devotion to Mary...John de Satge - much of whose work I admire - also mourns "the impression which Anglo-Saxons gain from visits to Catholic churches during holidays in Latin countries or in Ireland." As CRI complains of our "excessive devotion," de Satge winces at our "debased devotion" in paintings, hymns, and prayers, which he suggests are "sentimental."...On the whole, I would say to you, that if Latin sentiment seems treacly sentimentality to you, that is your problem. It is not ours. I believe that Protestantism itself unavoidably shows its Northern European origins. We can respect these, but dourness and a stiff upper lip are simply not our Catholic style. Why should they be? To supercilious and racist remarks about the Catholic Irish and the Catholic peoples of Southern Europe and Latin America, I say, give me a break!